“feel like artists”

or: In Attack and Defense of the Focusrite Scarlett Solo

A few weeks ago, I saw the following tweet:

The cynical subtext: prosumer artists’ tools companies are not just selling products, they’re also selling the dream of being a “real artist.”

An interesting economic dynamic underlies this: every product can be considered either a professional tool or a consumer product. In the former, the value-add of the product translates to revenue for the customer—they transform the value of the tool, however indirectly, into value for their customers. In the latter, the value-add is directly consumed by the customer. A professional tool is sold to a non-leaf node in a supply chain value tree, while a consumer product terminates in a leaf.

Professional tools vs. consumer products in the context of the B2B/B2C “value tree”

This difference often reveals itself in pricing structures. True professional tools—B2B SaaS comes to mind—will often stratify their pricing proportional to downstream revenue, often by number of seats, number of active users, or sometimes directly by the customer’s gross revenue. Consumer products are more often a flat rate across customers.

Top-of-the-line artists’ tools are professional tools. They are purchased by professional studios and leveraged by top-0.1-percentile artists to generate revenue that has a reasonable chance of exceeding the cost of the tool. Think the ARRI ALEXA or Neumann U87. However, most artists’ tools are a third thing: “prosumer.” These are products that are marketed as professional tools, but are truly consumer products, and are priced as such. There’s a bitter reality in this sleight of hand.

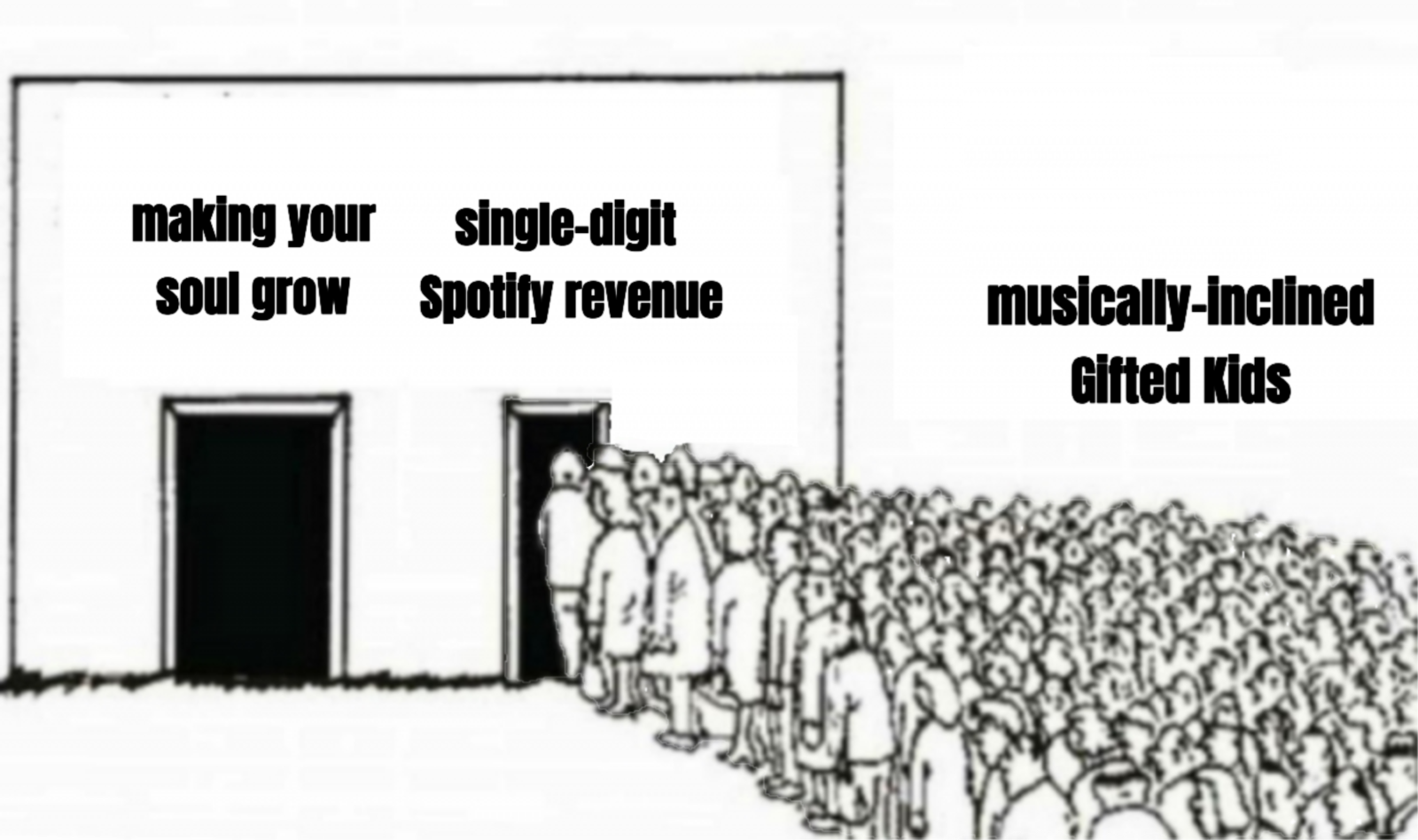

The “you can do anything” messaging from the parents of the 90s and 00s drives and haunts the artistically-inclined former Gifted Kids well into their 20s and 30s. An ocean of this archetype crowds the unbelievably narrow passageway to a sustainable artistic career. Prosumer products leverage the pressure of this crush. A diminishingly small proportion of the prosumer market turns their $200 audio interface or drawing tablet or embroidery machine into >$200 of revenue, but companies ignore this fact in their public messaging. They say with their marketing “this tool is an investment in your career” but choose pricing that appeals to an order of magnitude more people than will ever see financial returns from that “investment.” They are more interested in the crowd than the passageway. The members of the crowd, already practiced in self-deception, require little convincing.

As someone both pursuing semi-professional art-making and creating software tools for musicians, I can’t escape this reality nor the convention of deception around it. The resolution, I think, can be found in a note of advice from Kurt Vonnegut to a class of high schoolers in 2006. I highly recommend reading the full note. For our purposes, I’ll paraphrase:

“Do art and do it for the rest of your lives. Make it as good as you possibly can. But don’t tell anybody what you’re doing.

You will find that you have already been gloriously rewarded. You have experienced becoming, learned a lot more about what’s inside you, and you have made your soul grow.”

Better, I think, to accept this. To artists: resist the crush of the crowd fighting for scraps. Make art and make money and accept that those two things may best be kept separate. To artists’ tools companies: admit that your tools are consumer products. Resist, or explicitly refute, the common line: “this is an investment in your career”. Relieved of this deception, you are free to say something better: “this may help make your soul grow”.